LIKE other primitive races the peoples of Chaldea scarcely discriminated at all between religion and magic. One difference between the priest and the sorcerer was that the one employed magic for religious purposes whilst the other used it for his own ends. The literature of Chaldea—especially its religious literature—teems with references to magic, and in its spells and incantations we see the prototypes of those employed by the magicians of medireval Europe. Indeed so closely do some of the Assyrian incantations and magical practices resemble those of the European sorcerers of the Middle Ages and of primitive peoples of the present day that it is difficult to convince oneself that they are of independent origin.

In Chaldea as in ancient Egypt the crude and vague magical practices of primeval times received form and developed into accepted ritual, just as early religious ideas evolved into dogmas under the stress of theological controversy and opinion. As there were men who would dispute upon religious questions, so were there persons who would discuss matters magical. This is not to say that the terms ‘religion’ and ‘magic’ possessed any well-defined boundaries for them. Nor is it at all clear that they do for us in this twentieth century. They overlap ; and it has long been the belief of the writer that their relations are but represented by two circles which intersect one another and the areas of which partially coincide.

The writer has outlined his opinions regarding the origin of magic in an earlier volume of this series, and has little to add to what he then wrote, except that he desires to lay stress upon the identification of early religion and magic. It is only when they begin to evolve, to branch out, that the two systems present differences. If there is any one circumstance which accentuates the difference more than another it is that the ethical element does not enter into magic in the same manner as it does into religion.

That Chaldean magic was the precursor of European mediaeval magic as apart from popular sorcery and witchcraft is instanced not only by the similarity between the systems but by the introduction into mediaeval magic of the names of Babylonian and Assyrian gods and magicians. Again and again is Babylon appealed to even more frequently than Egypt, and we meet constantly with the names of Beelzebub, Ishtar (as Astarte), Baal, and Moloch, whilst the names of demons, obviously of Babylonian origin, are encountered in almost every work on the subject. Frequent allusions are also made to the ‘wise men’ and necromancers of Babylon, and to the ‘ star-gazers ’ of Chaldea. The conclusion is irresistible that ceremonial magic, as practised in the Middle Ages, owed much to that of Babylon.

Our information regarding Chaldean magic is much more complete than that which we possess concerning the magic of ancient Egypt. Hundreds of spells, incantations, and omen-inscriptions have been recovered, and these not only enlighten us regarding the class of priests who practised magic, but they tell us of the several varieties of demons, ghosts, and evil spirits ; they minutely describe the Babylonian witch and wizard, and they picture for us jnany magical ceremonies, besides informing us of the names of scores of plants and flowers possessing magical properties, of magical substances, jewels, amulets, and the like. Also they speak of sortilege or the divination of the future, of the drawing of magical circles, of the exorcism of evil spirits, and the casting out of demons.

The Roots of Science

In these Babylonian magical records we have by far the most complete picture of the magic of the ancient world. It is a wondrous story that is told by those bricks and cylinders of stamped clay —the story of civilized man’s first gropings for light. For in these venerable writings we must recognize the first attempts at scientific elucidation of the forces by which man is surrounded. Science, like religion, has its roots deep in magic. The primitive man believes implicitly in the efficacy of magical ritual. What it brings about once it can bring about again if the proper conditions be present and recognized. Thus it possesses for the barbarian as much of the element of certainty as the scientific process does for the chemist or the electrician. Given certain causes certain effects must follow. Surely, then, in the barbarous mind, magic is pseudo-scientific—of the nature of science.

There appears a deeper gloom, a more ominous spirit of the ancient and the obscure in the magic of old Mesopotamia than in that of any other land. Its mighty sanctuaries, its sky-aspiring towers, seem founded upon this belief in the efficacy of the spoken spell, the reiterated invocation. Thousands of spirits various and grotesque, the parents of the ghosts and goblins of a later day, haunt the purlieus of the^temple, battening upon the remains of sacrifice (the leavings of the gorged gods), flit through the night-bound streets, and disturb the rest of the dwellers in houses. Demons with claw and talon, vampires, ghouls—all are there. Spirits blest and unblest, jinn, witch-hags, lemures, sorrowing unburied ghosts. No type of supernatural being appears to have been unknown to the imaginative Semites of old Chaldea. These must all be ‘ laid/ exorcised, or placated, and it is not to be marvelled at that in such circumstances the trade of the necromancer flourished exceedingly. The witch or wizard, however, the unprofessional and detached practitioner with no priestly status, must beware. He or she was regarded with suspicion, and if one fell sick of a strange wasting or a disease to which he could not attach a name, the nearest sorcerer, male or female, real or imaginary, was in all probability brought to book.

Priestly Wizards

There were at least two classes of priests who dealt in the occult—the barû , or seers, and the asipû, or wizards. The caste of the barû was a very ancient one, dating at least from the time of Khammurabi. The barû performed divination by consulting the livers of animals and also by observation of the flight of birds. We find many of the kings of Babylonia consulting this class of soothsayer. Sennacherib, for example, sought from the barû the cause of his father’s violent death.

The asipû, on the other hand, was the remover of taboo and bans of all sorts; he chanted the rites described in the magical texts, and performed the ceremony of atonement.

He that stilleth all to rest, that pacifieth all.

By whose incantations everything is at peace.

The gods are upon his right hand and his left, they are behind and before him.

The wizard and the witch were known as Kassapu or Kassaptu. These were the sorcerers or magicians proper, and that they were considered dangerous to the community is shown by the manner in which they are treated by the code of Khammurabi, in which it is ordained that he who charges a man with sorcery and can justify the charge shall obtain the sorcerer’s house, and the sorcerer shall plunge into the river. But if the sorcerer be not drowned then he who accused him shall be put to death and the wrongly accused man shall have his house.

A series of texts known as ‘Maklu’ provides us, among other things, with a striking picture of the Babylonian witch. It tells how she prowls the streets, searching for victims, snatching love from handsome men, and withering beauteous women. At another time she is depicted sitting in the shade of the wall making spells and fashioning images. The suppliant prays that her magic may revert upon herself, that the image of her which he has made, and doubtless rendered into the hands of the priest, shall be burnt by the fire-god, that her words may be forced back into her mouth. “May her mouth be fat, may her tongue be salt,” continues the prayer. The haltafpen-ftlant along with sesame is sent against her. “0, witch, like the circlet of this seal may thy face grow green and yellow !”

An Assyrian text says of a sorceress that her bounds are the whole world, that she can pass over all mountains. The writer states that near his door he has posted a servant, on the right and left of his door has he set Lugalgirra and Allamu, that they might kill the witch.

The library of Assur-bani-pal contains many cuneiform tablets dealing with magic, but there are also extant many magical tablets of the later Babylonian Empire. These were known to the Babylonians by some name or word, indicative perhaps of the special sphere of their activities. Thus we have the Maklu (‘burning’), Surpu (‘consuming’), Utukki limnûti (‘evil spirits ’), and Labartu (‘witch-hag ’) series, besides many other texts dealing with magical practices.

The Maklu series deals with spells against witches and wizards, images of whom are to be consumed by fire to the accompaniment of suitable spells and prayers. The Surpu series contains prayers and incantations against taboo. That against evil spirits provides the haunted with spells which will exorcise demons, ghosts, and the powers of the air generally, and place devils under a ban. In other magical tablets the diseases to which poor humanity is prone are guarded against, and instructions are given on the manner in which they may be transferred to the dead bodies of animals, usually swine or goats.

|

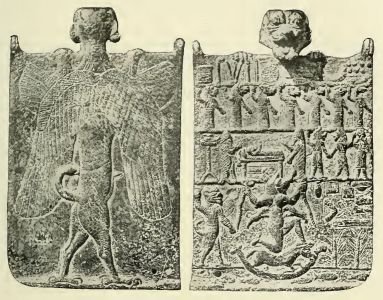

| Image: Exorcising Demons of Disease |

The Word of Power

As in Egypt, the word of power was held in great reverence by the magicians of Chaldea, who believed that the name, preferably the secret name, of a god possessed sufficient force in its mere syllables to defeat and scatter the hordes of evil things that surrounded and harassed mankind. The names of Ea and Merodach were, perhaps, most frequently used to carry destruction into the ranks of the demon army. It was also necessary to know the name of the devil or person against whom his spells were directed. If to this could be added a piece of hair, or the nail-parings in the case of a human being, then special efficacy was given to the enchantment. But just as hair or nails were part of a man so was his name, and hence the great virtue ascribed to names in art-magic, ancient and modern. The name was, as it were, the vehicle by means of which the magician established a link between himself and his victim, and the Babylonians in exorcising sickness or disease of any kind were wont to recite long catalogues of the names of evil spirits and demons in the hope that by so doing they might chance to light upon that especial individual who was the cause of the malady. Even long lists of names of persons who had died premature deaths were often recited in order to ensure that they would not return to torment the living.

Babylonian Vampires

In all lands and epochs the grisly conception of the vampire has gained a strong hold upon the imagination of the common people, and this was no less the case in Babylonia and Assyria than elsewhere. There have not been wanting those who believed that vampirism was confined to the Slavonic race alone, and that the peoples of Russia, Bohemia, and the Balkan Peninsula were the sole possessors of the vampire legend. Recent research, however, has exposed the fallacy of this theory and has shown that, far from being the property of the Slavs or even of Aryan peoples, this horrible belief is or was the possession of practically every race, savage or civilized, that is known to anthropology. The seven evil spirits of Assyria are, among other things, vampires of no uncertain type.

An ancient poem which was chanted by them commences thus :

Seven are they ! Seven are they !

In the ocean deep, seven are they !

Battening in heaven, seven are they !

Bred in the depths of the ocean ;

Not male nor female are they,

But are as the roaming wind-blast.

No wife have they, no son can they beget;

Knowing neither mercy nor pity,

They hearken not to prayer, to prayer.

They are as horses reared amid the hills,

The Evil Ones of Ea ;

Throne-bearers to the gods are they,

They stand in the highway to befoul the path ;

Evil are they, evil are they !

Seven are they, seven are they,

Twice seven are they !

Destructive storms (and) evil winds are they,

An evil blast that heraldeth the baneful storm,

An evil blast, forerunner of the baleful storm.

They are mighty children, mighty sons,

Heralds of the Pestilence.

Throne-bearers of Ereskigal,

They are the flood which rusheth through the land.

Seven gods of the broad earth,

Seven robber(?)-gods are they,

Seven gods of might,

Seven evil demons,

Seven evil demons of oppression,

Seven in heaven and seven on earth.

Spirits that minish heaven and earth,

That minish the land,

Spirits that minish the land,

Of giant strength,

Of giant strength and giant tread,

Demons (like) raging bulls, great ghosts,

Ghosts that break through all houses,

Demons that have no shame,

Seven are they !

Knowing no care, they grind the land like corn;

Knowing no mercy, they rage against mankind,

They spill their blood like rain,

Devouring their flesh (and) sucking their veins.

. . . . . . .

They are demons full of violence, ceaselessly devouring blood.

This last line clearly indicates their character as vampires. They are akin to the Rakshasas of India or the arch-dcmons of Zoroastrianism. Such demons are also to be seen in the Polynesian tii, the Malayan hantu penyadin, a dog-headed water-demon, and the kephu of the Karens, which under the form of a wizard’s head and stomach devours human souls.

Tylor considers vampires to be

“causes conceived in spiritual form to account for specific facts of wasting disease.”

Afanasief regards them as thunder-gods and spirits of the storm, who during winter slumber in their cloud-coffins to rise again in spring and draw moisture from the clouds. But this theory will scarcely recommend itself to anyone with even a slight knowledge of mythological science. The Abbe Calmet’s difficulty in believing in vampires was that he could not understand how a spirit could leave its grave and return thence with ponderable matter in the form of blood, leaving no traces showing that the surface of the earth above the grave had been stirred. But this view might be solved by the occult theory of the ‘precipitation of matter’!

The Speaking Head

The targum of Jonathan Ben Uzziel gives the following version:

“And Rachel stole the images of her father; for they had murdered a man, who was a first-born son, and, having cut off his head, they embalmed it with salt and spices, and they wrote divinations upon a plate of gold, and put it under his tongue and placed it against the wall, and it conversed with them, and Laban worshipped it. And Jacob stole the science of Laban the Syrian, that he might not discover his departure.”

The Persian translation gives us astrolabes instead of teraphim, and implies that they were instruments used for judicial astrology, and that Rachel stole them to prevent her father from discovering their route. At all events the teraphim were means of divination among believers and unbelievers ; they were known among the Egyptians and among Syrians. What makes it extremely probable that they were not objects of religious worship is, that it does not appear from any other passage of Scripture that Laban was an idolater; besides which Rachel, who was certainly a worshipper of the true God, took them, it seems, on account of their supposed supernatural powers. It must, however, be observed that some have supposed these teraphim to have been talismans for the cure of diseases ; and others, that being really idols, Rachel stole them to put a stop to her father’s idolatry. There is a not very dissimilar account related (Judges xviii) of Micah and his teraphim, which seems sufficient to prove that the use of them was not considered inconsistent with the profession of the true religion.

Gods once Demons

Many of the Babylonian gods retained traces of their primitive demoniacal characteristics, and this applies to the great triad, Ea, Anu, and En-lil, who probably evolved into godhead from an animistic group of nature spirits. Each of these gods was accompanied by demon groups. Thus the disease-demons were ‘ the beloved sons of Bel,’ the fates were the seven daughters of Anu, and the seven storm-demons the children of Ea. In a magical incantation describing the primitive monster form of Ea it is said that his head is like a serpent’s, the ears are those of a basilisk, his horns are twisted into curls, his body is a sun-fish full of stars, his feet are armed with claws, and the sole of his foot has no heel.

Ea was ‘the great magician of the gods’; his sway over the forces of nature was secured by the performance of magical rites, and his services were obtained by human beings who performed requisite ceremonies and repeated appropriate spells. Although he might be worshipped and propitiated in his temple at Eridu, he could also be conjured in mud huts. The latter, indeed, as in Mexico, appear to have been the oldest holy places.

The Legend of Ura

It is told that Ura, the dread demon of disease, once made up his mind to destroy mankind. But Ishnu, his counsellor, appeased him so that he abandoned his intention, and he gave humanity a chance of escape. Whoever should praise Ura and magnify his name would, he said, rule the four quarters of the world, and should have none to oppose him. He should not die in pestilence, and his speech should bring him into favour with the great ones of the earth. Wherever a tablet with the song of Ura was set up, in that house there should be immunity from the pestilence.

As we read in the closing lines of the Gilgamesh epic, the dead were often left unburied in Babylonia, and the ghosts of those who were thus treated were, as in more modern times and climes, supposed to haunt the living until given proper sepulture. They roamed the streets and byways seeking for sustenance among the garbage in the gutters, and looking for haunted houses in which to dwell, denied as they were the shelter of the grave, which was regarded as the true ‘home’ of the dead. They frequently terrified children into madness or death, and bitterly mocked those in tribulation. They were, in fact, the outcasts of mortality, spiteful and venomous because they had not been properly treated. The modern race which most nearly approximates to the Babylonian in its treatment of and attitude to the dead seems to be the Burmese, who are extremely circumspect as to how they speak and act towards the inhabitants of the spirit-world, as they believe that disrespect or mockery will bring down upon them misfortune or disease. An infinite number of guardian spirits is included in the Burman demonological system. These dwell in their houses and are the tutelars of village communities, and even of clans. These are duly propitiated, at which ceremonies rice, beer, and tea-salad are offered to them. Women are employed as exorcists for driving out the evil spirits.

Purification

Purification by water entered largely into Babylonian magic. The ceremony known as the ‘Incancation of Eridu,’ so frequently alluded to in Babylonian magical texts, was probably some form of purification by water, relating as it does to the home of Ea, the sea-god. Another ceremony prescribes the mingling of water from a pool ‘that no hand hath touched,’ with tamarisk, mastakal, ginger, alkali, and mixed wine. Therein must be placed a shining ring, and the mixture is then to be poured upon the patient. A root of saffron is then to be taken and pounded with pure salt and alkali and fat of the matku-bird brought from the mountains, and with this strange mixture the body of the patient is to be anointed.

The Chamber of the Priest-Magician

Let us attempt to describe the treatment of a case by a priest-physician-magician of Babylonia. The proceeding is rather a recondite one, but by the aid of imagination as well as the assistance of Babylonian representation we may construct a tolerably clear picture. The chamber of the sage is almost certain to be situated in some nook in one of those vast and imposing fanes which more closely resembled cities than mere temples. We draw the curtain and enter a rather darksome room. ^ The atmosphere is pungent with chemic odours, and ranged on shelves disposed upon the tiled walls are numerous jars, great and small, containing the fearsome compounds which the practitioner applies to the sufferings of Babylonian humanity. The asipu, shaven and austere, asks us what we desire of him, and in the role of Babylonian citizens we acquaint him with the fact that our lives are made miserable for us by a witch who sends upon us misfortune after misfortune, now the blight or some equally intractable and horrible disease, now an evil wind, now unspeakable enchantments which torment us unceasingly. In his capacity of physician the asipu examines our bodies, shrunken and exhausted with fever or rheumatism, and having prescribed for us, compounds the mixture with his own hands and enjoins us to its regular application. He mixes various ingredients in a stone mortar, whispering his spells the while, with many a prayer to Ea the beneficent and Merodach the all-powerful that we may be restored to health. Then he promises to visit us at our dwelling and gravely bids us adieu, after expressing the hope that we will graciously contribute to the upkeep of the house of religion to which he is attached.

Leaving the darkened haunt of the asipu for the brilliant sunshine of a Babylonian summer afternoon, we are at first inclined to forget our fears, and to laugh away the horrible superstitions, the relics of barbarian ancestors, which weigh us down. But as night approaches we grow more fearful, we crouch with the children in the darkest corner of our clay-brick dwelling, and tremble at every sound. The rushing of the wind overhead is for us the noise of the Labartu, the hag-demon, come hither to tear from tis our little ones, or perhaps a rat rustling in the straw may seem to us the Alu-demon. The ghosts of the dead gibber at the threshold, and even pale Uni, lord of disease, himself may glance in at the tiny window with ghastly countenance and eager, red eyes. The pains of rheumatism assail us. Ha, the evil witch is at work, thrusting thorns into the waxen images made in our shape that we may suffer the torment brought about by sympathetic magic, to which we would rather refer our aches than to the circumstance that we dwell hard by the river-swamps.

A loud knocking resounds at the door. We tremble anew and the children scream. At last the dread powers of evil have come to summon us to the final ordeal, or perhaps the witch herself, grown bold by reason of her immunity, has come to wreak fresh vengeance. The flimsy door of boards is thrown open, and to our unspeakable relief the stern face of the asipu appears beneath the flickering light of the taper. We shout with joy, and the children cluster around the priest, clinging to his garments and clasping his knees.

The Witch-Finding

The priest smiles at our fear, and motioning us to sit in a circle produces several waxen figures of demons which he places on the floor. It is noticeable that these figures all appear to be bound with miniature ropes. Taking one of these in the shape of a Labartu or hag-demon, the priest places before it twelve small cakes made from a peculiar kind of meal. He then pours out a libation of water, places the image of a small black dog beside that of the witch, lays a piece of the heart of a young pig on the mouth of the figure and some white bread and a box of ointment beside it.

He then chants something like the following :

“May a guardian spirit be present at my side when I draw near unto the sick man, when I examine his muscles, when I compose his limbs, when I sprinkle the water of Ea upon him. Avoid thee whether thou art an evil spirit or an evil demon, an evil ghost or an evil devil, an evil god or an evil fiend, hag-demon, ghoul, sprite, phantom, or wraith, or any disease, fever, headache, shivering, or any sorcery, spell, or enchantment.”

Having recited some such words of power the asipu then directs us to keep the figure at the head of our bed for three nights, then to bury it beneath the earthen floor. But alas ! no cure results. The witch still torments us by day and night, and once more we have recourse to the priest-doctor; the ceremony is gone through again, but still the family health does not improve. The little ones suffer from fever, and bad luck consistently dogs us. After a stormy scene between husband and wife, who differ regarding the qualifications of the asipu, another practitioner is called in. He is younger and more enterprising than the last, and he has not yet learned that half the business of the physician is to ‘nurse ’ his patients, in the financial sense of the term. Whereas the elderly asipu had gone quietly home to bed after prescribing for us, this young physician, who has his spurs to win, after being consulted goes home to his clay surgery and hunts up a likely exorcism.

Next day, armed with this wordy weapon, he arrives at our dwelling and, placing a waxen image of the witch upon the floor, vents upon it the full force of his rhetoric. As he is on the point of leaving, screams resound from a neighbouring cabin. Bestowing upon us a look of the deepest meaning our asipu darts to the hut opposite and hales forth an ancient crone, whose appearance of age and illness give her a most sinister look. At once we recognize in her a wretch who dared to menace our children when in innocent play they cast hot ashes upon her thatch and introduced hot swamp water into her cistern. In righteous wrath we lay hands on the abandoned being who for so many months has cast a blight upon our lives. She exclaims that the pains of death have seized upon her, and we laugh in triumph, for we know that the superior magic of our asipu has taken effect. On the way to the river we are joined by neighbours, who rejoice with us that we have caught the witch. Great is the satisfaction of the party when at last the devilish crone is cast headlong into the stream.

But ere many seconds pass we begin to look incredulously upon each other, for the wicked one refuses to sink. This means that she is innocent! Then, awful moment, we find every eye directed upon us, we who were so happy and light-hearted but a moment before. We tremble, for we know how severe are the laws against the indiscriminate accusation of those suspected of witchcraft. As the ancient crone continues to float, a loud murmuring arises in the crowd, and with quaking limbs and eyes full of terror we snatch up our children and make a dash for freedom.

Luckily the asipu accompanies us so that the crowd dare not pursue, and indeed, so absurdly changeable is human nature, most of them are busied in rescuing the old woman. In a few minutes we have placed all immediate danger of pursuit behind us. The asipu has departed to his temple, richer in the experience by the lesson of a false ‘prescription.’ After a hurried consultation we quit the town, skirt the arable land which fringes it, and plunge into the desert. She who was opposed to the employment of a young and inexperienced asipu does not make matters any better by reiterating “I told you so.” And he who favoured a ‘second opinion,’ on paying a night visit to the city, discovers that the ‘witch ’ has succumbed to her harsh treatment; that his house has been made over to her relatives by way of compensation, and that a legal process has been taken out against him. Returning to his wife he acquaints her with the sad news, and hand in hand with their weeping offspring they turn and face the desert.

The Magic Circle

The magic circle, as in use among the Chaldean sorcerers, bears many points of resemblance to that described in mediaeval works on magic. The Babylonian magician, when describing the circle, made seven little winged figures, which he set before an image of the god Nergal. After doing so he stated that he had covered them with a dark robe and bound them with a coloured cord, setting beside them tamarisk and the heart of the palm, that he had completed the magic circle and had surrounded them with a sprinkling of lime and flour.

That the magic circle of mediaeval times must have been evolved from the Chaldean is plain from the strong resemblance between the two. Directions for the making of a mediaeval magic circle are as follows :—

In the first place the magician is supposed to fix upon a spot proper for such a purpose, which must be either in a subterranean vault, hung round with black, and lighted by a magical torch, or else in the centre of some thick wood or desert, or upon some extensive unfrequented plain, where several roads meet, or amidst the ruins of ancient castles, abbeys, or monasteries, or amongst the rocks on the seashore, in some private detached churchyard, or any other melancholy place between the hours of twelve and one in the night, either when the moon shines very bright, or else when the elements are disturbed with storms of thunder, lightning, wind, and rain; for, in these places, times, and seasons, it is contended that spirits can with less difficulty manifest themselves to mortal eyes, and continue visible with the least pain.

When the proper time and place are fixed upon, a magic circle is to be formed within which the master and his associates are carefully to retire. The reason assigned by magicians and others for the institution and use of the circles is, that so much ground being blessed and consecrated by holy words and ceremonies has a secret force to expel all evil spirits from the bounds thereof, and, being sprinkled with sacred water, the ground is purified from all uncleanness ; beside the holy names of God being written over every part of it, its force becomes proof against all evil spirits.

Babylonian Demons

Babylonian demons were legion and most of them exceedingly malevolent. The Utukku was an evil spirit that lurked generally in the desert, where it lay in wait for unsuspecting travellers, but it did not confine its haunts to the more barren places, for it was also to be found among the mountains, in graveyards, and even in the sea. An evil fate befel the man upon whom it looked.

The Rabisu is another lurking demon that secretes itself in unfrequented spots to leap upon passers-by. The Labartu, which has already been alluded to, is, strangely enough, spoken of as the daughter of Anu. She was supposed to dwell in the mountains or in marshy places, and was particularly addicted to the destruction of children. Babylonian mothers were wont to hang charms round their children’s necks to guard them against this horrible hag.

The Sedu appears to have been in some senses a guardian spirit and in others a being of evil propensities. It is often appealed to at the end of invocations along with the Lamassu, a spirit of a similar type. These malign influences were probably the prototypes of the Arabian jinn, to whom they have many points of resemblance.

Many Assyrian spirits were half-human and halfsupernatural, and some of them were supposed to contract unions with human beings, like the Arabian jinn. The offspring of such unions was supposed to be a spirit called Alu, which haunted ruins and deserted buildings and indeed entered the houses of men like a ghost to steal their sleep. Ghosts proper were also common enough, as has already been observed, and those who had not been buried were almost certain to return to harass mankind. It was dangerous even to look upon a corpse, lest the spirit or edimmu of the dead man should seize upon the beholder. The Assyrians seemed to be of the opinion that a ghost like a vampire might drain away the strength of the living, and long formulae were in existence containing numerous names of haunting spirits, one of which it was hoped would apply to the tormenting ghost, and these were used for the purposes of exorcism. To lay a spirit the following articles were necessary : seven small loaves of roast corn, the hoof of a dark-coloured ox, flour of roast corn, and a little leaven. The ghosts were then asked why they tormented the haunted man, after which the flour and leaven were kneaded into a paste in the horn of an ox and a small libation poured into a hole in the earth. The leaven dough was then placed in the hoof of an ox, and another libation poured out with an incantation to the god Shamash. In another case figures of the dead man and the living person to whom the spirit has appeared are to be made and libations poured out before both of them, then the figure of the dead man is to be buried and that of the living man washed in pure water, the whole ceremony being typical of sympathetic magic, which thus supposed the burial of the body of the ghost and the purification of the living man. In the morning incense was to be offered up before the Sun-god at his rising, when sweet woods were to be burned and a libation of sesame wine poured out.

If a human being was troubled by a ghost, it was necessary that he should be anointed with various substances in order that the result of the ghostly contact might be nullified.

An old text says,

“When a ghost appeareth in the house of a man there will be a destruction of that house. When it speaketh and hearkeneth for an answer the man will die, and there will be lamentation.”

Taboo

The belief in taboo was universal in ancient Chaldea. Amongst the Babylonians it was known as mamit. There were taboos on many things, but especially upon corpses and uncleanness of all kinds. We find the taboo generally alluded to in a text “as the barrier that none can pass.”

Among all barbarous peoples the taboo is usually intended to hedge in the sacred thing from the profane person or the common people, but it may also be employed for sanitary reasons. Thus the flesh of certain animals, such as the pig, may not be eaten in hot countries. Food must not be prepared by those who are in the slightest degree suspected of uncleanness, and these laws are usually of the most rigorous character ; but should a man violate the taboo placed upon certain foods, then he himself often became taboo. No one might have any intercourse with him. He was left to his own devices, and, in short, became a sort of pariah. In the Assyrian texts we find many instances of this kind of taboo, and numerous were the supplications that these might be removed. If one drank water from an unclean cup he had violated a taboo. Like the Arab he might not “lick the platter clean.” If he were taboo he might not touch another man, he might not converse with him, he might not pray to the gods, he might not even be interceded for by anyone else. In fact he was excommunicate. If a man cast his eye upon water which another person had washed his hands in, or if he came into contact with a person who had not yet performed his ablutions, he became unclean. An entire purification ritual was incumbent on any Assyrian who touched or even looked upon a dead man.

It may be asked, wherefore was this elaborate cleanliness essential to avoid taboo ? The answer undoubtedly is—because of the belief in the power of sympathetic magic. Did one come into contact with a person who was in any way unclean, or with a corpse or other unpleasant object, he was supposed to come within the radius of the evil which emanated from it.

Popular Superstitions

The superstition that the evil-eye of a witch or a wizard might bring blight upon an individual or community was as persistent in Chaldea as elsewhere. Incantations frequently allude to it as among the causes of sickness, and exorcisms were duly directed against it. Even to-day, on the site of the ruins of Babylon children are protected against it by fastening small blue objects to their headgear.

Just as mould from a grave was supposed by the witches of the Middle Ages to be particularly efficacious in magic, so was the dust of the temple supposed to possess hidden virtue in Assyria. If one pared one’s nails or cut one’s hair it was considered necessary to bury them lest a sorcerer should discover them and use them against their late owner ; for a sorcery performed upon a part was by the law of sympathetic magic thought to reflect upon the whole. A like superstition attached to the discarded clothing of people, for among barbarian or uncultured folk the apparel is regarded as part and parcel of the man. Even in our own time simple and uneducated people tear a piece from their garments and hang it as an offering on the bushes around any of the numerous healing wells in the country that they may have journeyed to. This is a survival of the custom of sacrificing the part for the whole.

If one desired to get rid of a headache one had to take the hair of a young kid and give it to a wise woman, who would “spin it on the right side and double it on the left,” then it was to be bound into fourteen knots and the incantation of Ea pronounced upon it, after which it was to be bound round the head and neck of the sick man. For defects in eyesight the Assyrians wove black and white threads or hairs together, muttering incantations the while, and these were placed upon the eyes. It was thought, too, that the tongues of evil spirits or sorcerers could be ‘bound,’ and that a net because of its many knots was efficacious in keeping evilly-disposed magicians away.

Omens

|

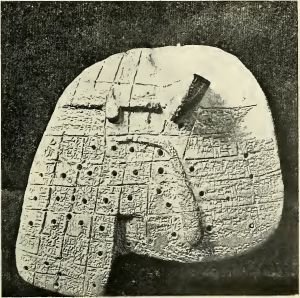

| Image right: Clay Object resembling a Sheep’s Liver; |

This is inscribed with magical formulae; it was probably used for purposes of divination, and was employed by the priests of Babylon in their ceremonies.

Divination as practised by means of augury was a rite of the first importance among the Babylonians and Assyrians. This was absolutely distinct from divination by astrology. The favourite method of augury among the Chaldeans of old was that by examination of the liver of a slaughtered animal. It was thought that when an animal was offered up in sacrifice to a god that the deity identified himself for the time being with that animal, and that the beast thus afforded a means of indicating the wishes of the god. Now among people in a primitive state of culture the soul is almost invariably supposed to reside in the liver instead of in the heart or brain. More blood is secreted by the liver than by any other organ in the body, and upon the opening of a carcase it appears the most striking, the most central, and the most sanguinary of the vital parts. The liver was, in fact, supposed by early peoples to be the fountain of the blood supply and therefore of life itself. Hepa-toscopy or divination from the liver was undertaken by the Chaldeans for the purpose of determining what the gods had in mind. The soul of the animal became for the nonce the soul of the god, therefore if the signs of the liver of the sacrificed animal could be read the mind of the god became clear, and his intentions regarding the future were known. The animal usually sacrificed was a sheep, the liver of which animal is most complicated in appearance. The two lower lobes are sharply divided from one another and are separated from the upper by a narrow depression, and the whole surface is covered with markings and fissures, lines and curves which give it much the appearance of a map on which roads and valleys are outlined. This applies to the freshly excised liver only, and these markings are never the same in any two livers.

Certain priests were set apart for the practice of liver-reading, and these were exceedingly expert, being able to decipher the hepatoscopic signs with great skill. They first examined the gall-bladder, which might be reduced or swollen. They inferred various circumstances from the several ducts and the shapes and sizes of the lobes and their appendices. Diseases of the liver, too, particularly common among sheep in all countries, were even more frequent among these animals in the marshy portions of the Euphrates Valley.

The literature connected with this species of augury is very extensive, and Assur-bani-pal’s library contained thousands of fragments describing the omens deduced from the practice. These enumerate the chief appearances of the liver, as the shade of the colour of the gall, the length of the ducts, and so forth. The lobes were divided into sections, lower, medial, and higher, and the interpretation varied from the phenomena therein observed. The markings on the liver possessed various names, such as ‘palaces,’ ‘weapons,’ ‘paths,’ and ‘feet,’ which terms remind us somewhat of the bizarre nomenclature of astrology. Later in the progress of the art the various combinations of signs came to be known so well, and there were so many cuneiform texts in existence which afforded instruction in them, that a liver could be quickly ‘read’ by the barû or reader, a name which was afterward applied to the astrologists as well and to those who divined through various other natural phenomena.

One of the earliest instances on record of hepato-scopy is that regarding Naram-Sin, who consulted a sheep’s liver before declaring war. The great Sargon did likewise, and we find Gudea applying to his ‘liver inspectors ’ when attempting to discover a favourable time for laying the foundations of the temple of Nin-girsu. Throughout the whole history of the Babylonian monarchy in fact, from its early beginnings to its end, we find this system in vogue. Whether it was in force in Sumerian times we have no means of knowing, but there is every likelihood that such was the case.

The Ritual of Hepatoscopy

Quite an elaborate ritual grew up around the readings of the omens by the examination of the liver. The baru who officiated must first of all purify himself and don special apparel for the ceremony. Prayers were then offered up to Shamash and Hadad or Rammon, who were known as the ‘lords of divination.’ Specific questions were usually put. The sheep selected for sacrifice must be without blemish, and the manner of slaughtering it and the examination of its liver must be made with the most meticulous care. Sometimes the signs were doubtful, and upon such occasions a second sheep was sacrificed.

Nabonidus, the last King of Babylon, on one occasion desired to restore a temple to the moon-god at Harran. He wished to be certain that this step commended itself to Merodach, the chief deity of Babylonia, so he applied to the ‘liver inspectors’ of his day and found that the omen was favourable. We find him also desirous of making a certain symbol of the sun-god in accordance with an ancient pattern. He placed a model of this before Shamash and consulted the liver of a sheep to ascertain whether the god approved of the offering, but on three separate occasions the signs were unfavourable. Nabonidus then concluded that the model of the symbol could not have been correctly reproduced, and on replacing it by another he found the signs propitious. In order, however, that there should be no mistake he sought among the records of the past for the result of a liver inspection on a similar occasion, and by comparing the omens he became convinced that he was safe in making a symbol.

Peculiar signs, when they were found connected with events of importance, were specially noted in the literature of liver divination, and were handed down from generation to generation of diviners. Thus a number of omens are associated with Gilga-mesh, the mythical hero of the Babylonian epic, and a certain condition of the gall-bladder is said to indicate “the omen of Urumush, the king, whom the men of his palace killed.”

Bad signs and good signs are enumerated in the literature of the subject. Thus like most peoples the Babylonians considered the right side as lucky and the left as unlucky. Any sign on the right side of the gall-bladder, ducts or lobes, was supposed to refer to the king, the country, or the army, while a similar sign on the sinister side applied to the enemy. Thus a good sign on the right side applied to Babylonia or Assyria in a favourable sense, a bad sign on the right side in an unfavourable sense. A good sign on the left side was an omen favourable to the enemy, whereas a bad sign on the left side was, of course, to the native king or forces.

It would be out of place here to give a more extended description of the liver-reading of the ancient Chaldeans. Suffice it to say that the subject is a very complicated one in its deeper significance, and has little interest for the general reader in its advanced stages. Certain well-marked conditions of the liver could only indicate certain political, religious, or personal events. It will be more interesting if we attempt to visualise the act of divination by liver reading, as it was practised in ancient Babylonia, and if our imaginations break down in the process it is not the fault of the very large material they have to work upon.

The Missing Caravan

The ages roll back as a scroll, and I see myself as one of the great banker-merchants of Babylon, one of those princes of commerce whose contracts and agreements are found stamped upon clay cylinders where once the stately palaces of barter arose from the swarming streets of the city of Merodach. I have that morning been carried in my litter by sweating slaves, from my white house in a leafy suburb lying beneath the shadow of the lofty temple-city of Borsippa. As I reach my place of business I am aware of unrest, for the financial operations in which I engage are so closely watched that I may say without self-praise that I represent the pulse of Babylonian commerce. I enter the cool chamber where I usually transact my business, and where a pair of officious Persian slaves commence to fan me as soon as I take my seat. My head clerk enters and makes obeisance with an expression on his face eloquent of important news. It is as I expected—as I feared. The caravan from the Persian Gulf due to arrive at Babylon more than a week ago has not yet made its appearance, and although I had sent scouting parties as far as Ninnur, these have returned without bringing me the least intelligence regarding it.

I feel convinced that the caravan with my spices, woven fabrics, rare woods, and precious stones will never come tinkling down the great central street to deposit its wealth at the doors of my warehouses ; and the thought renders me so irritable that I sharply dismiss the Persian fan-bearers, and curse again and again the black-browed sons of Elam, who have doubtless looted my goods and cut the throats of my guards and servants. I go home at an early hour full of my misfortune. I cannot eat my evening meal. My wife gently asks me what ails me, but with a growl I refuse to enlighten her upon the cause of my annoyance.

Still, however, she persists, and succeeds in breaking down my surly opposition.

“Why trouble thy heart concerning this thing when thou mayest know what has happened to thy goods and thy servants ? Get thee to-morrow to the Baru, and he will enlighten thee,”

she says.

I start. After all, women have sense. There can be no harm in seeing the Baru and asking him to divine what has happened to my caravan. But I bethink me that I am wealthy, and that the priests love to pluck a well-feathered pigeon. I mention my suspicions of the priestly caste in no measured terms, to the distress of my devout wife and the amusement of my soldier-son.

Restlessly I toss upon my couch, and after a sleepless night feel that I cannot resume my business with the fear of loss upon me. So without breathing a word of my intention to my wife, I direct my litter-slaves to carry me to the great temple at Borsippa.

Arrived there, I enquire for the chief Baru. He is one of the friends of my youth, but for years our paths have diverged, and it is with surprise that he now greets me. I acquaint him with the nature of my dilemna, and nodding sympathetically he assures me that he will do his utmost to assist me. Somewhat reassured, I follow him into a tiled court near the far end of which stands a large altar. At a sign from him two priests bring in a live sheep and cut its throat. They then open the carcase and extract the liver. Immediately the chief Baru bends his grey head over it. For a long time he stares at it with the keenest attention. I begin to weary, and my old doubts regarding the sacerdotal caste return. At last the grey head rises from the long inspection, and the Baru turns to me with smiling face.

“The omen is good, my son,” he says, with a cheerful intonation.

“The compass and the hepatic duct are short. Thy path will be protected by thy Guardian Spirit, as will the path of thy servants. Go, and fear not.”

He speaks so definitely and his words are so reassuring that I seize him by the hands, and, thanking him effusively, take my leave. I go down to my warehouses in a new spirit of hopefulness and disregard the disdainful or pitying looks cast in my direction. I sit unperturbed and dictate contracts and letters of credit to my scribe.

Ha ! what is that ? By Merodach, it is—it is the sound of bells ! Up I leap, upsetting the wretched scribe who squats at my feet, and trampling upon his still wet clay tablets, I rush to the door. Down the street slowly advances a travel-worn caravan, and at the head of it there rides my trusty brown-faced captain, Babbar. He tumbles out of the saddle and kneels before me, but I raise him in a close embrace. All my goods, he assures me, are intact, and the cause of delay was a severe sickness which broke out among his followers. But all have recovered and my credit is restored.

As I turn to re-enter my warehouse with Babbar, a detaining hand is placed on my shoulder. It is a messenger from the chief Baru.

“My brother at the temple saw thy caravan coming from afar,” he says politely,

“and his message to thee, my son, is that, since thou hast so happily recovered thine own, thou shouldst devote a tithe of it to the service of the gods.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

The power is in knowing that you are the center of the universe